Original title: "Build What's Fundable"

Original author: Kyle Harrison

Compiled by: Jia Huan, ChainCatcher

In 2014, I sold my first company. It wasn't a huge sum, but at the time it felt like all the wealth I needed for a long time. After that, I felt pulled in several different directions. I've written about one of those paths before, and the self-discovery that led me to venture capital. But there was another pull, making me want to build something else.

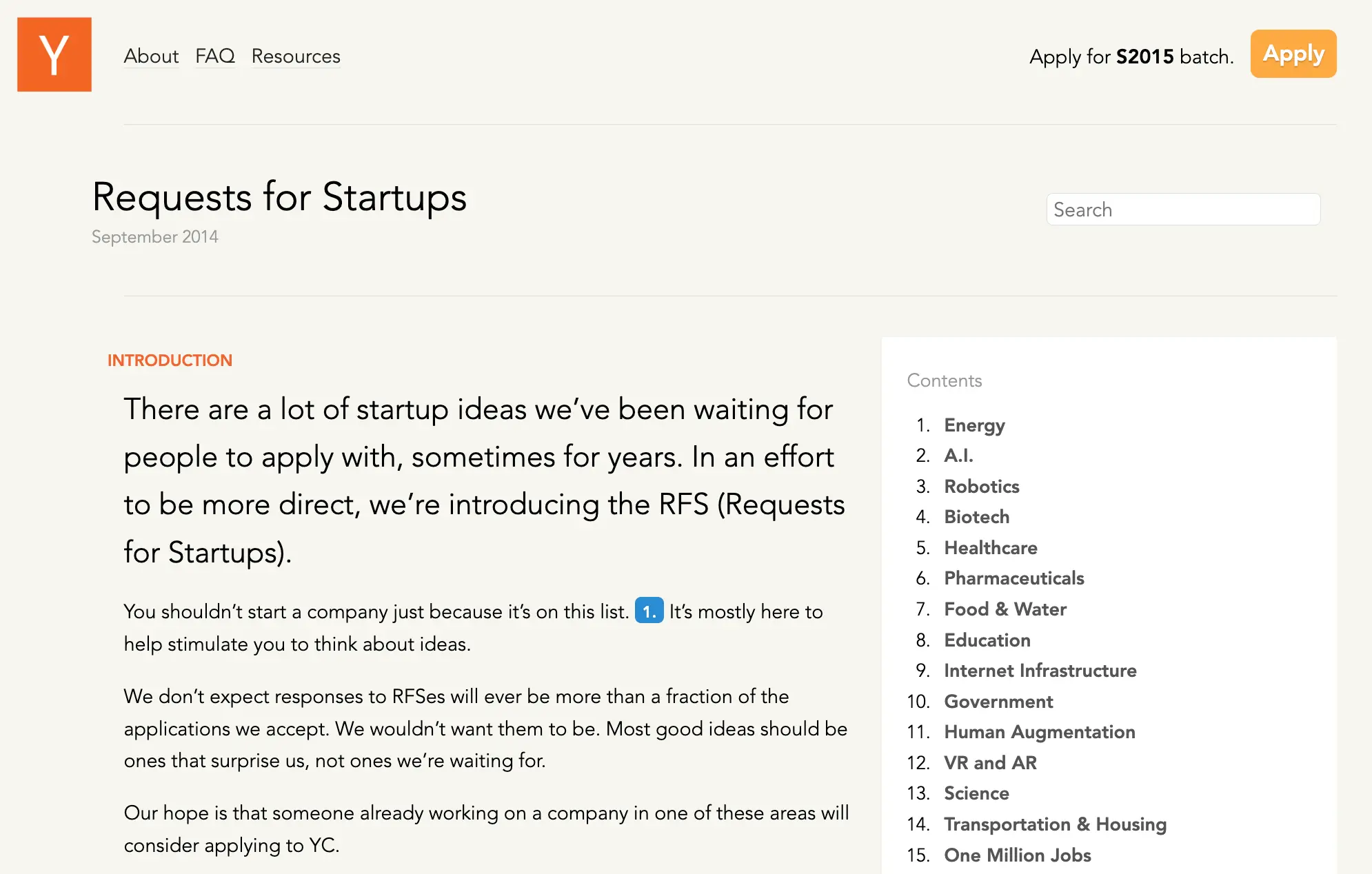

I didn't want to start a business just for the sake of starting a business; I wanted it to be more meaningful, to find a worthwhile problem to solve. While searching for a meaningful problem, I stumbled upon Y Combinator's (YC) RFS (Request for Proposals) list.

I remember being deeply inspired. It felt like a series of ambitious, problem-oriented questions waiting to be answered. For example, the opportunity to find new energy sources that are cheaper than anything before; exploring robots from space to the human body; and Norman Borlau-esque food innovation. It was this compelling vision that led me to start my second company: dedicated to promoting solar energy in Africa.

Before we begin, an important disclaimer: I have never applied to YC. I have never attended a YC roadshow. I only watched one of its online presentations during the pandemic. I have invested in a few companies that have participated in YC. I have only visited their Mountain View office once. For most of my career, I have been neither a die-hard YC fan nor a critic of YC. They are simply a small part of the vast and beautiful world we call the “tech world.”

But it wasn't until earlier this year that I saw this tweet, which made me start thinking: 11 years later, how is that list of startup proposals doing now?

So I did my research. What I found made me extremely sad. Dempsey was right, at least reflected in the shift in focus of the RFS list—from "problem-first" questions to "consensus-driven" ideas. Video generation, multi-agent infrastructure, AI-native enterprise SaaS, replacing government advisors with LLMs, forward-deployed agent modules, and so on. It's like taking millions of tweets from venture capital Twitter and generating a word cloud.

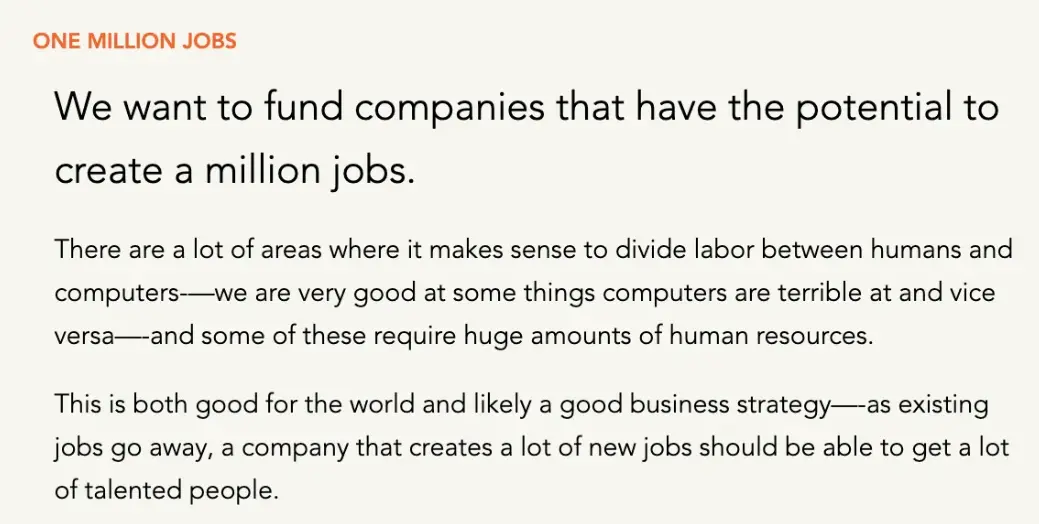

Back in 2014, I remember being struck by YC's entry on "One Million Jobs": ever since, I've often thought that in the US, only Walmart (and later Amazon) truly employs one million people. That's incredibly difficult! In a world where jobs are disappearing, this prompt aimed to explore what kind of business model could employ one million people. It's very thought-provoking!

So what about the version in the fall of 2025? It's "the first company with 10 people and a value of $100 billion."

At first glance, it might seem similar. But it's the complete opposite (e.g., because of AI, hire as few people as possible!) and essentially says the "secret that can't be told" out loud.

"What problem are you trying to solve? Who cares! But a lot of VCs are talking about how crazy these 'revenue per employee' figures are getting, so... you know... just do it!"

This is Dempsey's comment. YC is becoming "the best window into the current mainstream consensus."

In fact, you could almost feel this startup search list morphing in real time around the "mainstream consensus." It was this disappointment with what was once an ambitious creation that led me down an intellectual "rabbit hole." I reflected on my understanding of Y Combinator's original purpose and why it was so valuable in its early years. At that time, the tech world was opaque, and Y Combinator represented the best entry point into it.

But then I realized the goal had shifted. As the tech industry became increasingly directional, Y Combinator became less focused on making the world more understandable and more on catering to consensus. "Give the ecosystem what it wants, and they're just playing the game within the existing rules." They were serving the needs of a much larger "consensus capital machine"—startups with a specific look and brilliance.

However, the poison of "chasing consensus" has spread from capital to cultural shaping. The prevalence of "normativity" has infected every aspect of our lives. With the demise of contrarian thinking, independent critical thinking has given way to a cultural adherence akin to party lines.

We can diagnose some of the problems arising from the evolution of YC. We can describe it as a symptom of a broader "normative consensus engine" spanning capital and culture.

But ultimately, there's only one problem. How do we solve it?

How can we break free from the shackles of conformity and rekindle the flame of personal struggle and independent thinking? Unfortunately, neither the "consensus capital machine" nor the halls of the "normative accelerator" (referring to Y Combinator) can be relied upon to help us.

From entry channels to manufacturing plants

When you look back at YC in the summer of 2005, you can see in the eyes of Paul Graham (YC founder, far right in the picture) a desire to mentor newcomers and a hopeful optimism. YC's initial vision was to serve as an "entry channel" for a startup ecosystem that was (at the time) extremely inaccessible.

In 2005, SaaS was still in its infancy. Mobile devices didn't exist yet. Entrepreneurship was far from a common career path. Technology was still an emerging upstart, not the dominant force in the world.

When Y Combinator first started, it had a clear opportunity to help demystify starting a business. The phrase "Build something people want" might seem obvious today, but in the early 2000s, the default business logic was more about feasibility studies and market analysts than "talking to customers." We take for granted many of the truths that YC helped popularize, demystifying the entrepreneurial journey for future generations.

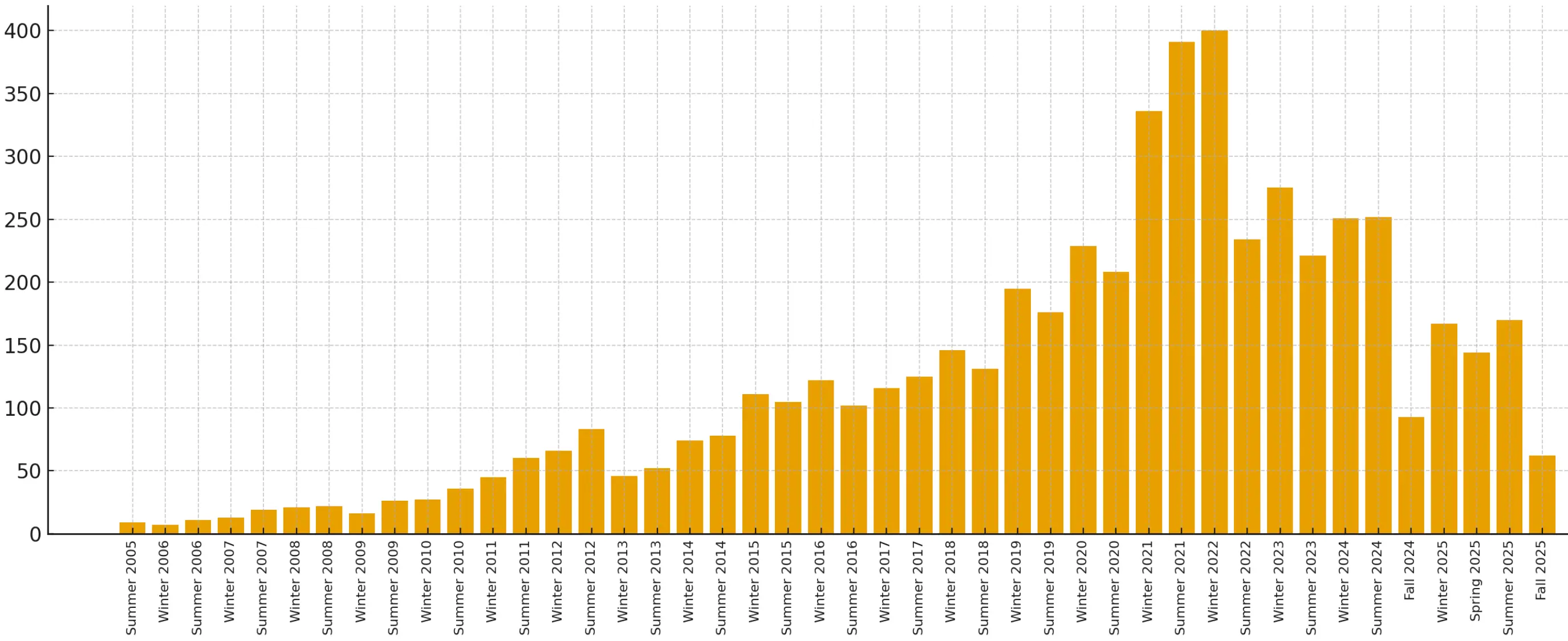

I have no doubt that Y Combinator was more beneficial than harmful to the world, at least for its first decade. But at some point, the rules of the game changed. Startups became less opaque; they became more understandable. Y Combinator could no longer simply unveil itself; it had to "mass-produce." The scale surged from 10-20 startups in the early years to over 100 in 2015, eventually peaking at 300-400 per batch in 2021 and 2022. While that number has declined somewhat, it still averages around 150 per batch today.

I believe Y Combinator's evolution has occurred in tandem with the changing "understandability" of the tech industry. The more easily the tech industry is understood, the less value Y Combinator can offer with its original operating model. Therefore, Y Combinator has adapted to this game. If technology is an increasingly clear path, then Y Combinator's mission is to get as many people as possible onto that path.

Convergence in “over-clarity”

Packy McCormick (founder and lead writer of Not Boring) introduced a word I use frequently now because it very effectively describes the world around us: "hyperlegible".

This concept suggests that, because we can access information from all sorts of content and learn about cultural nuances through social media, the world around us has become so highly transparent that it's almost tedious.

The technology industry is so “overly clear” that “Silicon Valley,” produced from 2014 to 2019, still depicts the cultural characteristics of a large group of people with remarkable accuracy.

In a world where the tech industry is so "overly transparent," Y Combinator's original mission to "reduce the industry's opacity" has been forced to evolve. While startups were once the go-to tool for rebels to break the mold, they are increasingly becoming a "funnel of consensus norms."

I'm not an anthropologist of the tech industry, but my interpretation is that this isn't a deliberate descent into complacency on YC's part. It's simply the path of least resistance. Startups are becoming more common and understood. For YC, a simple North Star (fundamental goal) is: "If we can help more and more companies get funding, we've succeeded!"

Those who secure funding today often look very similar to those who secured funding yesterday. This "standardization" is then observed among YC's founders and team.

A few days ago, I saw an analysis of statistics from the Y Combinator team:

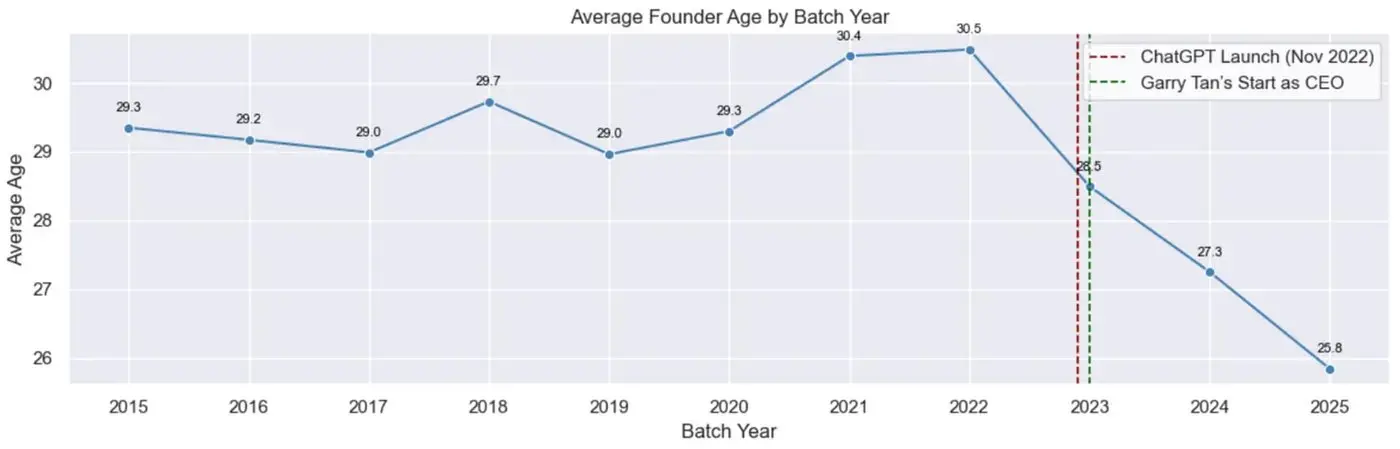

1. Younger demographic: The average age of YC's founders has decreased from 29-30 years old to approximately 25 years old now.

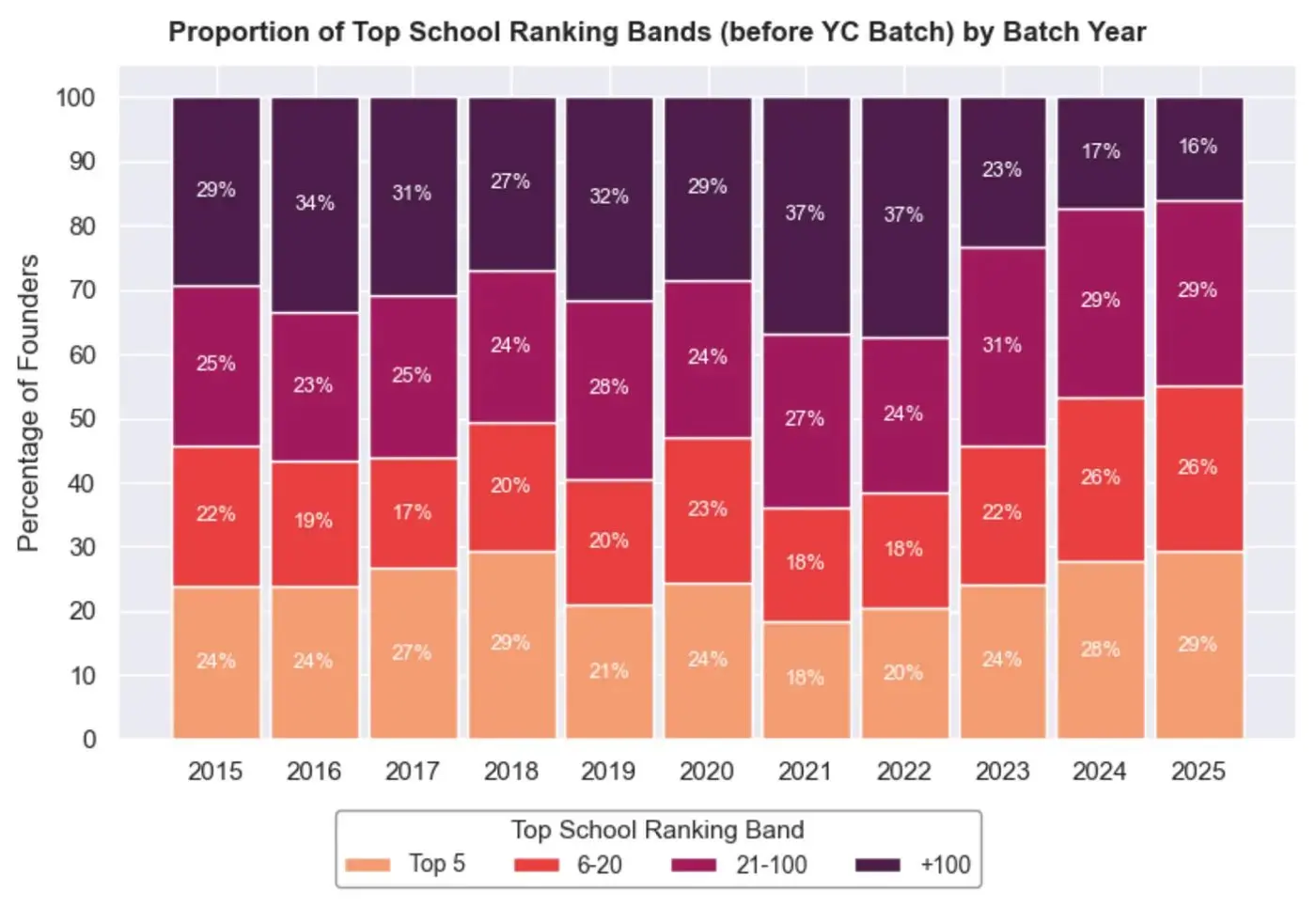

2. Elite Education: The proportion of founders who graduated from the top 20 universities has increased from approximately 46% in 2015 to 55% currently.

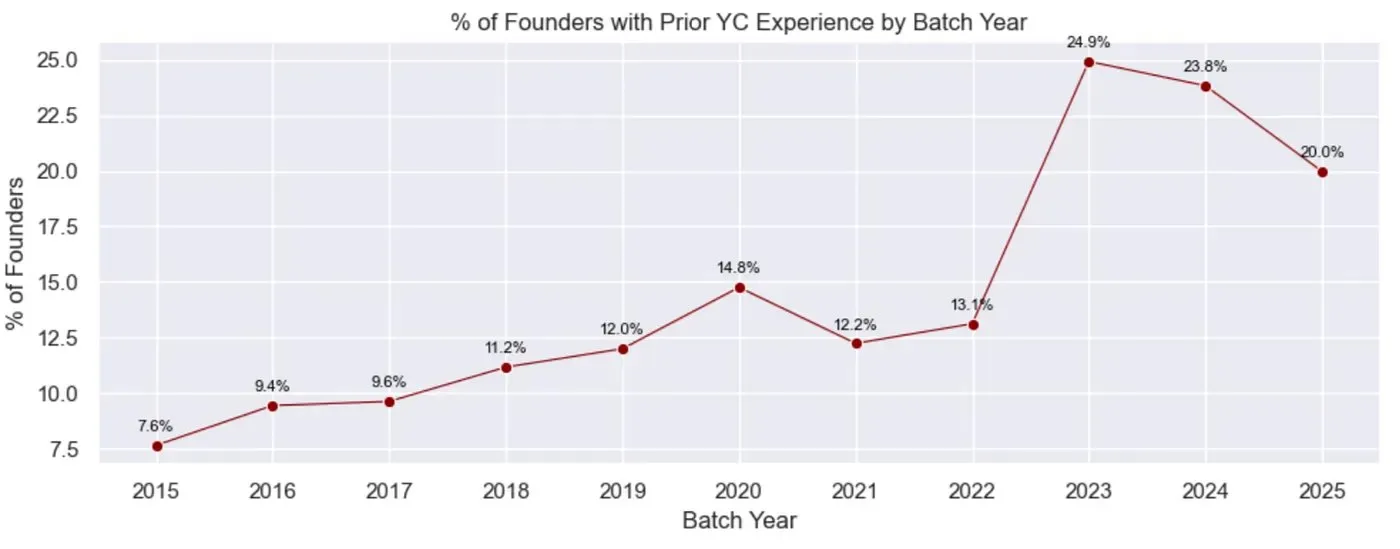

3. Returning YC Founders: The number of founders with prior YC experience increased from approximately 7-9% to approximately 20%.

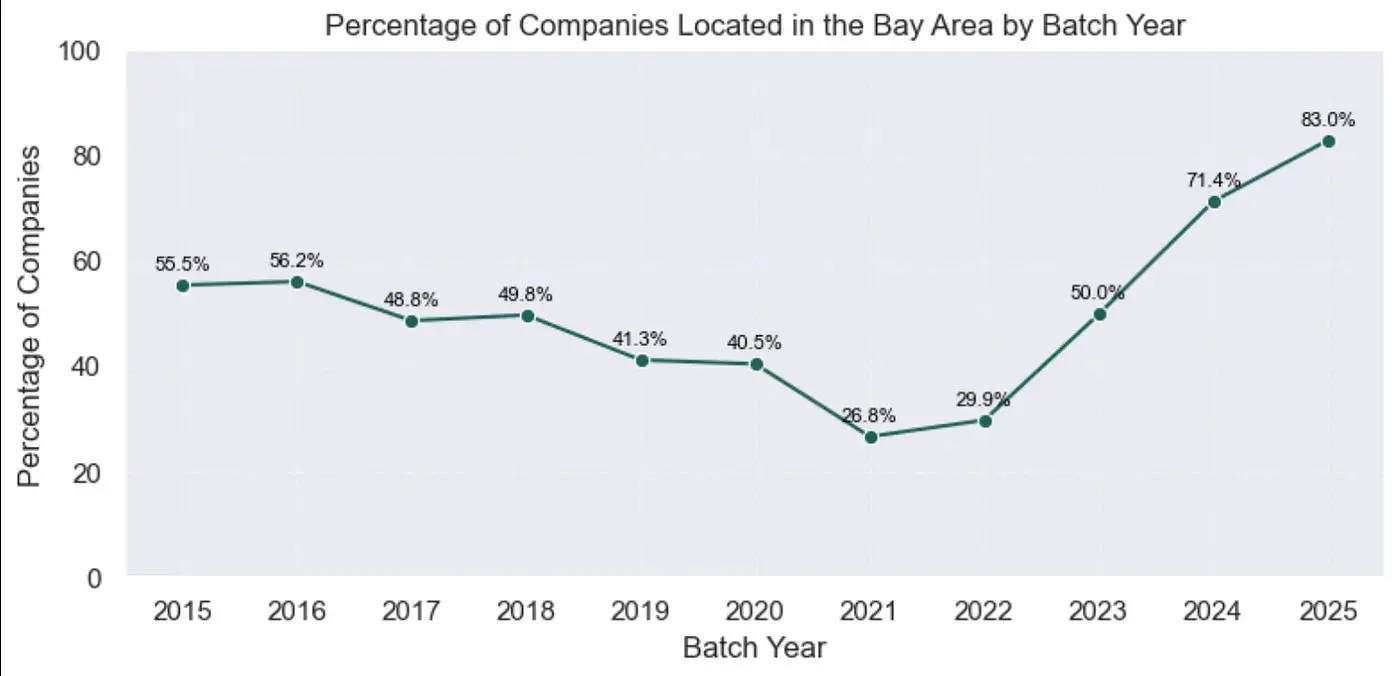

4. Concentrated in the San Francisco Bay Area: The proportion of Y Combinator founders headquartered in the Bay Area is even higher than before the pandemic, now reaching 83%.

Reflecting on these dynamics, they are only part of a larger story. Y Combinator has evolved from an "entry point" for opaque categories (such as technology) into something more like a "consensus-shaping machine."

It's not just the founders who are being shaped by consensus. You can almost see the entire YC team being molded around "mainstream consensus." As trends like voice assistants touch upon this consensus, you can see its reflection within the YC team.

Ironically, Paul Graham describes this consensus as a logical reflection of technological reality. I'm sure that's true. But I think the difference is that the consensus on "what gets investment" has become the ultimate goal of the entire operation, crowding out things that might have been more contrarian or unconventional in the past.

In early 2025, Y Combinator celebrated its 20th anniversary. During that celebration, it described its achievement as "creating $800 billion in startup market value." Note the emphasis on "created," not "helped" create billions of dollars in value. They view it as something they "created." Something they "manufactured." I believe Y Combinator's ultimate goal has shifted from "helping people understand how to build a company" to "maximizing the number of companies that pass through that funnel." While they may sound similar, they are not the same.

The most important takeaway here is that I don't believe it's YC's fault. Rather than blaming the entire industry on one participant, I'd rather say they were simply following a legitimate economic incentive shaped by a much larger force: the "consensus capital machine."

You must look like you're "worth investing in".

A few weeks ago, Roelof Botha (head of Sequoia Capital) stated in an interview that venture capital is not actually an asset class:

“If you look at the data, over the past 20-30 years, on average only 20 companies per year have ultimately achieved an exit value of $1 billion or more. Only 20. Despite more money flowing into the venture capital space, we haven’t seen a substantial change in the number of companies with those huge successes.”

Venture capital funding in 2024 reached $215 billion, up from $48 billion in 2014. Despite investing five times more capital, we didn't get five times the returns. But we're desperately trying to get more companies through that funnel. And in the venture capital engine, every loud, clear voice feeding the startup-making machine revolves around this idea: desperately trying to get more companies through a funnel that can no longer expand.

YC became complicit in this pursuit of a scalable model within an asset class that is inherently unscalable. The same applies to a16z. These engines, thriving on more capital, more companies, more hype, and more attention, are exacerbating the problem. In their pursuit of unscalability, they attempt to scale where it shouldn't. In business development, the greatest and most important achievements cannot be meticulously planned. And in the attempt to scale a company's formula, the "rough edges" of key ideas are worn away.

Just as Y Combinator's "startup proposal solicitation" has shifted from "problem-driven" ideas to "consensus-seeking" concepts, the formula for building startups reinforces a need: you have to look "investable" rather than build something "truly important." And this is increasingly evident not only in how companies are built, but also in how their cultures are shaped.

Normative Trends from Capital to Culture

Peter Thiel is widely praised for his numerous correct judgments. Interestingly, however, one of Thiel's most celebrated traits (such as being a contrarian investor/anti-consensus advocate) is another characteristic that allowed him to significantly outperform everyone else, and was once ridiculed as "clichéd and obvious." Yet, this trait is now becoming increasingly rare, almost extinct.

The relentless pursuit of consensus has poisoned every aspect of the company's development and is increasingly toxic to the way culture is built.

Venture capital, as a profession, also possesses the same "normative" characteristics. Starting a startup, joining Y Combinator, raising venture capital, building a "unicorn"—this has become the new-age version of "getting into a good school, finding a good job, and buying a house in the suburbs." It's a normative culture; it's the tried-and-tested, safe path. Social media and short videos only exacerbate this "programmable normativity" because we see these "overly clear life paths."

The most dangerous aspect of this approach is that it diminishes the public's need for critical thinking, because someone else has already done the thinking for you.

When I consider the true value of something, I often revisit Warren Buffett's famous quote about the market: "In the short run, it's a voting machine; in the long run, it's a weighing machine." However, the problem with a system that increasingly forms consensus, or even "manufactures" consensus, is that it becomes increasingly difficult to "weigh" the value of anything. That formation of consensus "invents" the value of specific assets, backgrounds, and experiences.

The same applies to the technology sector. This “normative mindset” of building around consensus-driven ideas is permeating the lives of millions and will have a negative impact on them, not only because they will create worse things, but also because they will be unable to develop independent thinking skills.

There are always some people who know this. They know that following the standard path will not yield the best results.

Be a Puritan-style founder

When reflecting on this cycle, the only answer I can think of is that we are facing a huge economic shock.

When you look at successful reverse engineering cases, you'll find that many were built by existing billionaires: Tesla, SpaceX, Palantir (a CIA data provider), and Anduril (a military drone company). I believe the lesson here isn't "become a billionaire first, then you can think independently." Rather, it prompts us to reflect on what "other traits" often lead to those outcomes.

In my view, another commonality among these companies is that they are led by “ideological purists”—those who believe in mission and dare to challenge consensus and authority.

Last week I wrote about "founder ideologies," and founders come in different types: missionaries, mercenaries, bards, and so on. Of all these types, one of the most important is the "missionary." The best founders usually come from this category.

The key takeaway here is that for a “normative culture” that is increasingly built around “consensus formation,” the only cure is to incentivize its participants to pursue ideological purity: to “believe” in something!

Y Combinator's motto has always been "Building products people want," which is a valid suggestion. However, what's even more important is "Building things worth building."

Embark on the right journey

The first element of becoming an intellectual Puritan is something I've written about repeatedly: embarking on the right path.

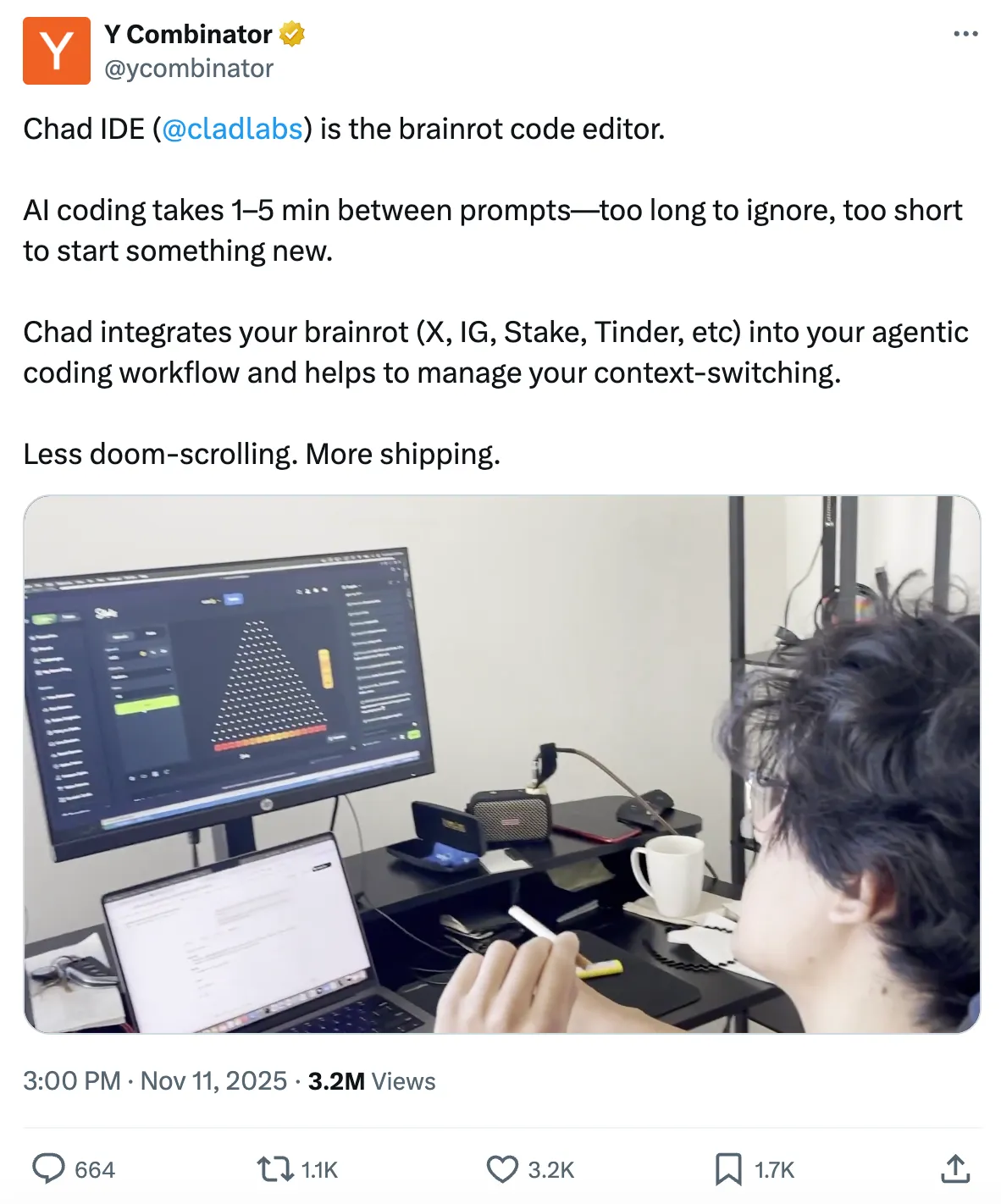

Last week, Y Combinator announced one of its latest investments: Chad IDE, a project that “erodes the brain.”

This product can integrate with your social media, dating apps, or gambling apps, so you can do other things while you wait for the code to load. That's fine, of course. Everyone knows we switch between tasks, jumping back and forth between mindless leisure and work.

But something was off, and the whole world noticed. One reaction from Chad IDE perfectly captured this shift in atmosphere:

Will O'Brien, founder of Ulysses, commented: "Venture capital funds that choose to support 'assembly line startups' like this and other ethically questionable startups should know that mission-driven founders will take notice and severely damage the company's reputation."

Assembly-line startups are steeped in nihilism. The founders and investors who back them are essentially saying: it doesn't matter. We should try to make money, even if it means producing utter garbage or encouraging evil. This infuriates mission-driven founders and generates a deep, insurmountable aversion when we consider partners.

The concept of "startups on the assembly line" is a natural extension of "pursuing scalable models in an asset class that cannot be scaled".

YC wasn't the only one to feel this shift in atmosphere.

Use it as an end in itself, not as a tool for others.

Technology itself is not a benevolent force. Technology, like any amorphous concept and collection of inanimate objects, is a tool.

It is those who wield technology that determine whether it produces good or bad results.

Incentives are the forces that drive people down a particular path (for better or for worse). But conviction, if unwavering, can transcend incentives when pursuing more important things.

My temptations might encourage me to lie, cheat, and steal, because these can make me financially wealthy. But my beliefs prevent me from becoming a slave to those temptations. They motivate me to live on a higher level.

Y Combinator (YC) initially served as an "entry point" to help people understand how to build technology. What they did with that ability was up to them. But as time went on, the incentives shifted, and scaling revealed its ugly side. As technology became an easier path to navigate, YC's goal shifted from "lighting up the path" to "getting as many people as possible onto that path."

From Y Combinator to giant venture capital firms, the pursuit of scale has enslaved many participants in the tech industry to incentives. The fear of failure further exacerbates this enslavement. We allow incentives to shape us because of fear—fear of poverty, fear of being stupid, or simply fear of being left behind. Fear of Missing Out (FOMO).

That fear leads us down the path of "normativity." We are assimilated. We seek conformity. We grind away the rough edges of our individuality until we are smoothed out to fit the "path of least resistance." But the path of least resistance has no room for "contrarian beliefs." In fact, it has no room for "any beliefs," because it fears that your beliefs will lead you down a path that consensus is unwilling to take.

But there are better ways. In a world of systems that seek norms, anchor yourself to beliefs. Find things worth believing in. Even if they are difficult. Even if they are unpopular. Find beliefs worth sacrificing for. Or, better yet, find beliefs worth living for.

Technology is a tool. Venture capital is a tool. Y Combinator is a tool. A16z is a tool. Attention is a tool. Anger is a tool. The good news is, tools abound. But only you can become a craftsman.

A hammer seeks nails. A saw seeks wood. But when you “believe” something is possible, it allows you to transcend the raw material and see the potential. See the angel in the marble, and then keep chiseling until you set him free.

We must never become tools of our tools. In this normative world that seeks consensus, there are countless incentives to enslave you. And if you don't have any particular "beliefs," they are very likely to succeed.

But for those who understand the reasons behind this, there will always be a better way.