By Janet Lorin

Compiled by: Luffy, Foresight News

A cryptocurrency data center in Piotr, Texas, located on land leased from the University of Texas system.

Dozens of wind turbines, each as tall as a 50-story building, stand against the desert sky. A total of 800,000 solar panels cover a scrubland almost the size of London's Heathrow Airport. In a cold-storage cryptocurrency data warehouse, rows of computer servers hum noisily across an area the size of two New York City blocks. The University of Texas system manages the land beneath all these new projects, and they are generating revenue for hundreds of thousands of students.

The University of Texas system has long relied on leasing its rights to its vast mineral underground in the Permian Basin to make money: extracting oil and gas from North America’s richest deposits. And miles of pipelines carrying “liquid gold” beneath windmills and solar farms remain the key to its wealth. Thanks to years of record fossil fuel production and investment gains, the University of Texas has a $47.5 billion endowment, the second largest in the college world, behind only Harvard University.

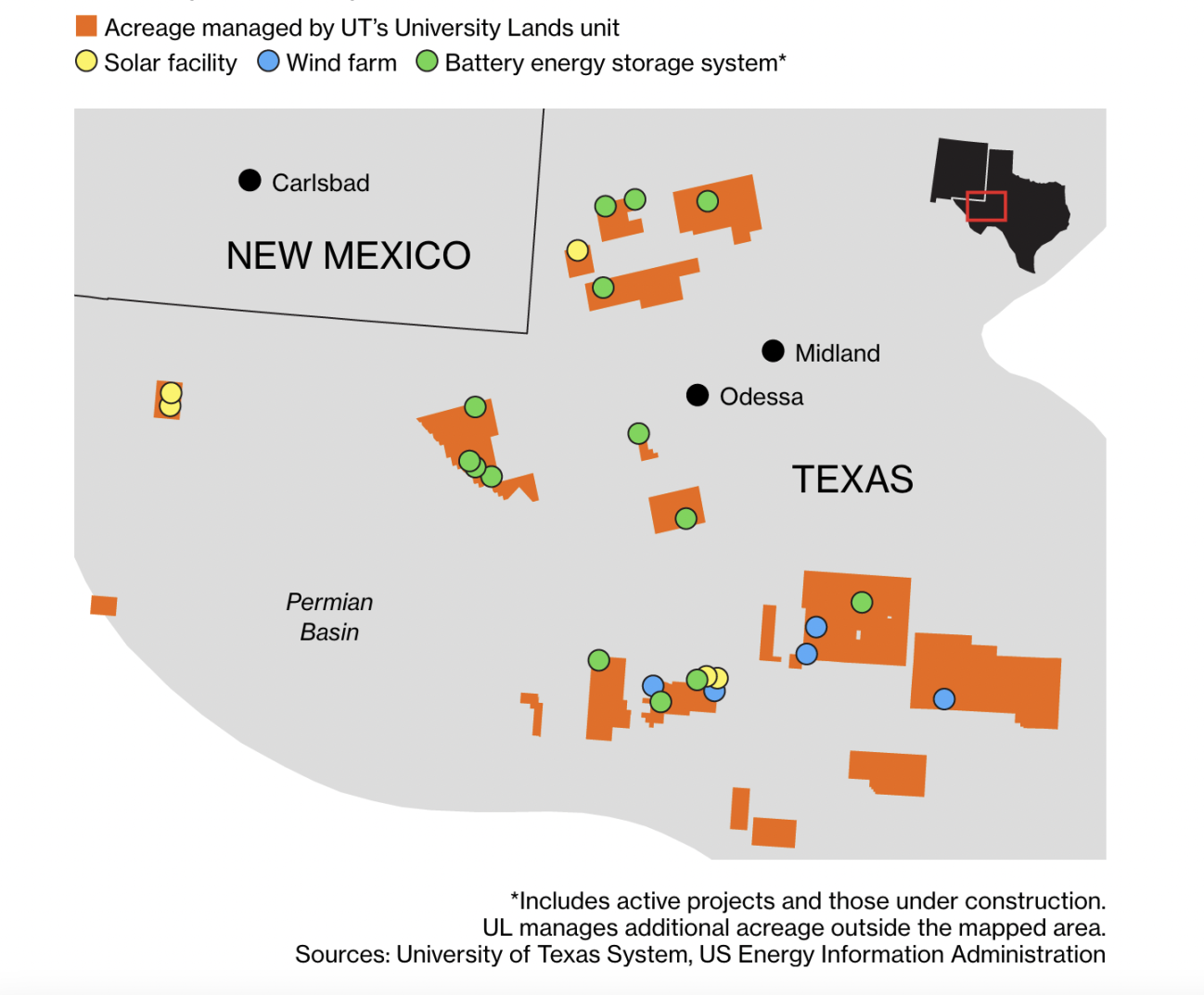

But the University of Texas system, which also manages the land for Texas A&M University, is increasingly looking to generate more revenue on the ground. Beyond ground development projects that began decades ago: leasing rights to build roads, power lines and pipelines, and use of fields for grazing, the university is now trying something new: leasing land for renewable energy, battery storage and cryptocurrency data centers, creating a revenue stream that barely existed five years ago.

A wind farm in Rankin, Texas.

In the year ended last August, these ground-based projects generated nearly $130 million in revenue, the most ever and about five times what it was 15 years ago. That was more than half of the scholarship and grant funding that year for the University of Texas at Austin, the state’s flagship campus.

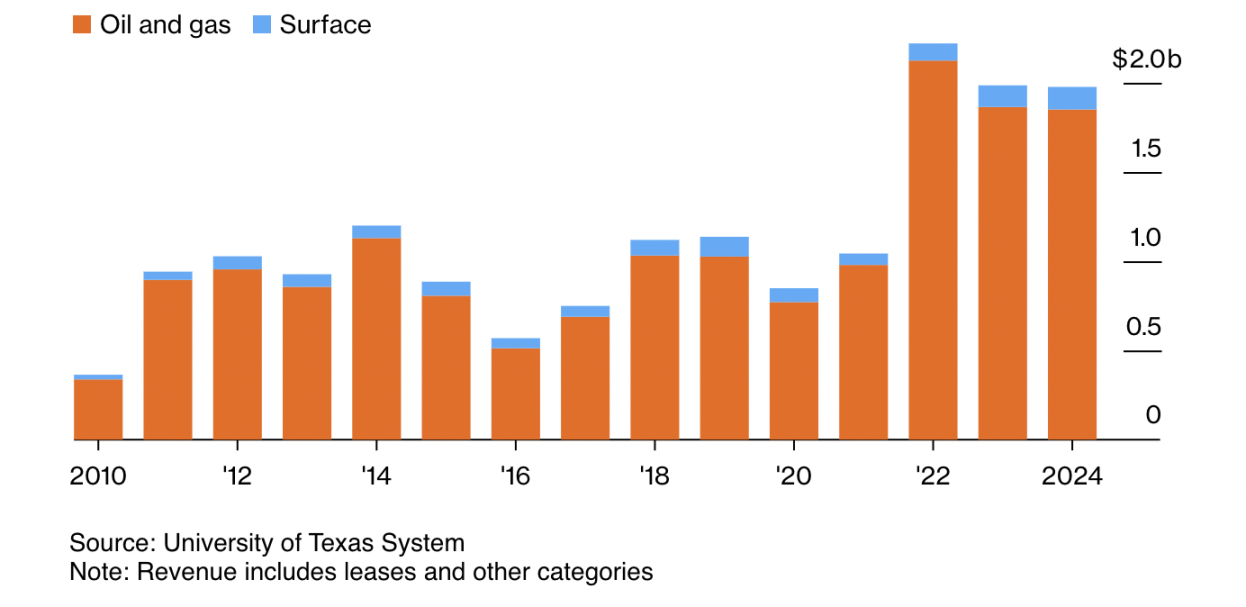

University of Texas System Land Holding Income (Years Ending August 31)

In May, the university reached a preliminary agreement to lease 200,000 acres, or 10% of its land holdings, to Virginia-based Apex Clean Energy for wind and solar power. The company’s clients include Facebook parent Meta and the U.S. Army. Although financial details have not been released, it would be the university’s largest ground-based project deal to date.

If such projects are successful, the University of Texas, which is seeking to host large data centers for artificial intelligence, companies that help utilities and others keep carbon emissions out of the atmosphere, and natural gas power plants, projects tens of millions of dollars in additional revenue annually for decades.

William Murphy Jr., CEO of University Lands, the UT division that manages state property, is trying to diversify the system’s revenue. Some oil company CEOs have said recently that U.S. production in the Permian Basin has reached or is near peak. “Our mission is to generate revenue for the institution in perpetuity. We have a long-term view, 30 to 50 years,” Murphy said. “We think this is a long race, and we’re at the beginning.”

William Murphy Jr., CEO of University Lands at the University of Texas, in his office in Houston.

The University of Texas strategy comes as renewable energy is under fire in Washington, D.C. In an effort to reverse the Biden administration's support for renewable energy, President Donald Trump, a fossil fuel advocate, has slammed wind turbines as unsightly and unreliable. "Big, ugly windmills — they ruin your community," he said in January.

Texas's own love-hate relationship with renewable energy could pose a challenge to the University of Texas's plans. The state is the largest wind power producer in the U.S. and ranks second in solar power, behind only California. "We believe in a 'full range' approach to energy development," Greg Abbott, the state's Republican governor, said in December.

To support this strategy in the Permian Basin, the Texas Public Utility Commission in April approved a $10.1 billion plan to build three transmission lines to help meet the needs of oil rigs, new data centers, cryptocurrency mines and hydrogen plants. "Without these new transmission lines, no one is going to want to expand wind and solar power in West Texas," said Ed Hirs, an energy economist at the University of Houston.

Yet after a devastating winter storm in 2021 caused massive blackouts, state Republicans blamed the grid’s reliance on wind and solar. Studies have found that failures at natural gas plants were the primary cause of the blackouts. Still, the Republican-controlled Texas Legislature is considering bills that would make it more expensive and difficult to build solar and wind projects.

Murphy said the university could change tack if state officials move away from renewable energy. For example, the university could support projects powered by natural gas. "If those incentives change, it could change the status quo in West Texas," he said. "We're not a political entity, we're not going to push anything."

Black-and-white photos of early oil rigs line the walls of Murphy’s Houston office, near ConocoPhillips’ headquarters and Shell’s main U.S. outpost in London. A wooden wheel from an old-fashioned oil pump dominates the office, twice as tall as Murphy, a sign that the University of Texas is still serious about making money from fossil fuels. “We plan to be around for a long time with oil and gas,” said Murphy, 47, a fifth-generation Texan who worked as an oil and gas lawyer and at one point managed one of the state’s largest cattle ranches.

An operator flares excess natural gas at a well on land managed by the University of Texas in Piot, Texas.

The University of Texas oversees 3,300 square miles of land in the Permian Basin, an area almost the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined, spanning 19 counties and centered on the famous oil town of Midland. In the 19th century, the state constitution granted the University of Texas mineral and surface mining rights to these lands. At the time, the arid land was considered of little value other than grazing. But drillers discovered oil in 1923, bringing wealth to Texas higher education.

The University of Texas does not explore for oil or gas itself, nor does it develop any projects on state lands. It leases those lands and collects royalties based on the amount of oil and gas produced. Over the past 15 years, land leased to oil and gas companies has generated $15.8 billion in revenue. Royalties have surged recently, to more than $2 billion a year, amid rising prices and production.

Renewable energy and energy storage projects on land managed by the University of Texas System

All that money goes into a fund that supports Texas' two big public universities. Two-thirds of it goes to the University of Texas and one-third to Texas A&M, which has a $20 billion endowment. Together, the two systems educate about 350,000 students. They also operate hospitals, including the University of Texas' MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

The state constitution requires that oil and gas revenues be used for capital expenditures, such as building classrooms, hospitals and labs, rather than day-to-day operations. The wealth has fueled a building boom, with $50 million recently allocated for a new cancer and surgery center at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, $60 million to fund a “smart hospital” with a virtual reality lab at the University of Texas at Arlington, and $54 million to support a new home for the Mays School of Business at the flagship campus of Texas A&M University.

New above-ground program revenue can be used for categories such as “academic excellence” and to support special initiatives. While still small compared with fossil fuel revenue, non-oil and gas revenue has totaled $1.2 billion over the past 15 years and has been rising sharply. Last November, the University of Texas system announced it would use its endowment, non-fossil fuel funds and other sources to waive tuition for all undergraduates on its nine campuses whose families earn $100,000 or less.

That kind of money is especially valuable to colleges today because it allows flexibility in a climate that’s unfavorable to higher education. The Trump administration has been going after elite colleges, cutting off federal funding for areas it doesn’t like, including anything seen as related to diversity, equity and inclusion. A Republican bill is seeking to tax the investment income of the largest private college endowments as much as 21%. As a public school system, the University of Texas isn’t in the crosshairs, and in any case its per capita endowment — the government’s measure of wealth — is too low, at about $230,000, compared with more than $2 million at Harvard.

Given its growing population and higher education enrollment, Texas remains hungry for more resources. Working with companies such as NextEra Energy, a renewable energy provider based in Juno Beach, Florida, the university has signed five wind and five solar leases. It also has four agreements for cryptocurrency mining and 14 for battery storage systems that are either in operation or under construction. Of the record $127 million in non-petroleum revenue last fiscal year, only $7 million came from renewable energy.

A cryptocurrency data center in Piot, Texas, located on land leased from the University of Texas system.

The biggest benefit may be leasing land for massive data centers, which have sparked controversy for their huge energy consumption. Tech companies have pledged to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to build them to meet the computing needs of artificial intelligence. “Texas is getting everyone’s attention,” said Brant Bernet, a senior vice president at CBRE Group who helps companies find land for data centers.

Murphy is striking these deals carefully because he doesn’t want to tie up too much land and forgo more lucrative opportunities. “We need to maximize returns, but we can’t rush it,” he said. “We understand the future, and we understand its potential.”