By The Economist

Translated by Centreless

One thing is clear: the idea that cryptocurrencies haven’t produced any innovation worth noting is long past its time.

In the eyes of the conservatives on Wall Street, the “use cases” of cryptocurrencies are often discussed with a sneer. The old hands have seen it all. Digital assets come and go, often with great fanfare, thrilling investors who are keen on memecoins and NFTs. Besides being used as tools for speculation and financial crime, their uses in other areas have also been repeatedly found to be flawed and inadequate.

The latest wave of enthusiasm, however, is different.

On July 18, President Donald Trump signed the GENIUS Act, providing stablecoins (crypto tokens backed by traditional assets, usually dollars) with the regulatory certainty that industry insiders have long desired. The industry is booming; Wall Streeters are now rushing to get involved. “Tokenization” is also on the rise: on-chain asset trading volumes are growing rapidly, including stocks, money market funds, and even private equity and debt.

As with any revolution, revolutionaries are ecstatic while conservatives are worried.

Vlad Tenev, CEO of digital asset broker Robinhood, said the new technology could “lay the foundation for cryptocurrencies to become the backbone of the global financial system.” European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde has a slightly different view. She worries that the emergence of stablecoins is tantamount to “the privatization of money.”

Both sides recognize the scale of the change at hand. For now, mainstream markets may be facing a more disruptive change than the early cryptocurrency speculation. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies promised to become digital gold, while tokens are just wrappers, or vehicles that represent other assets. It may not sound dramatic, but some of the most transformative innovations in modern finance have changed how assets are packaged, sliced and diced – exchange-traded funds (ETFs), Eurodollars and securitized debt are classic use cases.

Currently, there is $263 billion worth of stablecoins in circulation, up about 60% from a year ago. Standard Chartered expects the market to be worth $2 trillion in three years.

Last month, JPMorgan Chase, the largest U.S. bank, announced plans to launch a stablecoin-like product called the JPMorgan Deposit Token (JPMD), despite CEO Jamie Dimon’s long-standing skepticism of cryptocurrencies.

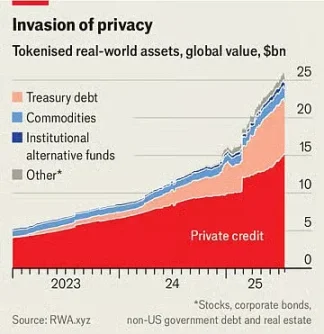

The market value of tokenized assets is only $25 billion, but it has more than doubled in the past year. On June 30, Robinhood launched more than 200 new tokens for European investors, allowing them to trade U.S. stocks and ETFs outside of normal trading hours.

Stablecoins make transactions cheap and fast because ownership is instantly registered on a digital ledger, eliminating the need for intermediaries to operate traditional payment channels. This is particularly valuable for cross-border transactions, which are currently costly and slow.

Although stablecoins currently account for less than 1% of global financial transactions, the GENIUS Act would help them. The bill confirms that stablecoins are not securities and requires that stablecoins be fully backed by safe, liquid assets.

Retail giants including Amazon and Walmart are reportedly considering launching their own stablecoins. To consumers, these stablecoins could be similar to gift cards, offering balances to spend at retailers, and potentially at lower prices. That would put an end to the likes of Mastercard and Visa, which make around 2% profit margins on sales facilitated in the U.S.

Tokenized assets are digital copies of another asset, whether a fund, company shares or a basket of commodities. Like stablecoins, they can make financial transactions faster and easier, especially those involving illiquid assets. Some products are just gimmicks. Why tokenize stocks? It might allow 24-hour trading, since the exchanges where the stocks are listed don’t have to be open, but the advantages of doing so are questionable. And for many retail investors, marginal transaction costs are already low or zero.

Efforts to tokenize

Many products, however, are not so fancy.

Take money market funds, for example, which invest in Treasury bills. Tokenized versions can double as a form of payment. Like stablecoins, these tokens are backed by safe assets and can be exchanged seamlessly on a blockchain. They’re also an investment that beats bank rates. The average interest rate on a U.S. savings account is less than 0.6%; many money-market funds yield as much as 4%. BlackRock’s largest tokenized money-market fund is now worth more than $2 billion.

“I expect that one day, tokenized funds will be as familiar to investors as ETFs,” the company’s CEO Larry Fink wrote in a recent letter to investors.

This will be disruptive to incumbent financial institutions.

Banks may be trying to get into new digital packaging, but they’re doing so in part because they realize tokens pose a threat. The combination of stablecoins and tokenized money-market funds could eventually make bank deposits less attractive.

If banks lose about 10% of their $19 trillion in retail deposits (the cheapest form of funding), their average funding costs would rise to 2.27% from 2.03%, the American Bankers Association noted. While total deposits, including business accounts, would not fall, bank margins would be squeezed.

These new assets could also be disruptive to the broader financial system.

Holders of Robinhood’s new equity tokens, for example, don’t actually own the underlying shares. Technically, they own a derivative that tracks the value of the asset (including any dividends paid by the company), not the shares themselves. As a result, they don’t get the voting rights that typically come with stock ownership. If the token issuer goes bankrupt, holders would be stuck fighting for ownership of the underlying assets with other creditors of the failed company. A similar situation happened to Linqto, a fintech startup that filed for bankruptcy earlier this month. The company had issued shares in private companies through special purpose vehicles. Buyers now don’t know if they own the assets they thought they did.

This is one of the biggest opportunities of tokenization, but it also poses the biggest difficulties for regulators. Pairing illiquid private assets with easily traded tokens opens up a closed market to millions of retail investors who have trillions of dollars to deploy. They can buy shares in the most exciting private companies that are currently out of reach.

This raises questions.

Institutions such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have far more influence over public companies than private companies, which is why the former are suitable for retail investors. Tokens representing private shares would turn once-private equity into assets that can be traded as easily as an ETF. But while ETF issuers promise to provide intraday liquidity by trading the underlying asset, token providers do not. At a large enough scale, tokens would effectively turn private companies into public companies without any of the disclosure requirements that are normally required.

Even pro-cryptocurrency regulators want to draw a line.

SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce, known as “Crypto Mom” for her friendly attitude toward digital currencies, stressed in a July 9 statement that tokens should not be used to circumvent securities laws. “Tokenized securities are still securities,” she wrote. Therefore, companies issuing securities must comply with disclosure rules, regardless of whether the securities are wrapped in a new cryptocurrency. While this makes sense in theory, the slew of new assets with new structures means that regulators will be in an endless state of catch-up in practice.

So there’s a paradox.

If stablecoins are truly useful, they will also be truly disruptive. The more tokenized assets become attractive to brokers, clients, investors, merchants and other financial firms, the more they will change finance in ways that are both exciting and worrisome. Whatever the balance, one thing is clear: the idea that cryptocurrencies have not yet produced any innovation worth noting is long past.