Author: Ray Dalio

Did you notice the Federal Reserve's announcement that it would stop quantitative tightening (QT) and launch quantitative easing (QE)? Although this is described as a technical operation, it is still an easing policy in any case—and it is one of the important indicators I follow to track the evolution of the "Great Debt Cycle" dynamics described in the previous book.

As Chairman Powell stated, "At some point, reserves need to grow gradually to match the size of the banking system and the size of the economy. Therefore, we will increase reserves at specific times." The specific increase deserves close attention. Given that the Federal Reserve has the responsibility of "controlling the size of the banking system" during bubble periods, we need to simultaneously monitor the pace at which it injects liquidity into emerging bubbles through interest rate cuts.

More specifically, if a significant expansion of the balance sheet occurs against the backdrop of lower interest rates and a high fiscal deficit, we would view it as a classic example of coordinated fiscal and monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury to monetize government debt. If, in this scenario, private lending and capital market credit creation remain strong, the stock market repeatedly hits new highs, credit spreads are nearing lows, unemployment is low, inflation is exceeding targets, and artificial intelligence stocks have already formed a bubble (which, according to my bubble indicator, is indeed the case), then in my view, the Federal Reserve is injecting stimulus into the bubble.

Given the government and numerous advocacy for a significant easing of policy constraints to implement aggressive, capitalist growth-oriented monetary and fiscal policies, and the urgent need to address the massive outstanding deficits, debt, and bond supply and demand issues, I suspect this is far more than just a technical problem—a concern that should be understood. I understand the Federal Reserve's high level of concern about funding market risks, which means that in the current political environment, it tends to prioritize market stability over aggressively combating inflation. However, whether this will evolve into a full-blown, classic stimulus-driven quantitative easing (accompanied by large-scale net bond purchases) remains to be seen.

We should not overlook the fact that when the supply of US Treasury bonds exceeds demand, the central bank purchases bonds through "money printing," and the Treasury shortens debt maturities to make up for the shortfall in long-term bond demand, these are typical dynamic characteristics of the late stage of a debt cycle. Although I have fully explained its operating mechanism in my book "Why Nations Go Bankrupt: The Great Cycle," it is still necessary to point out that we are currently approaching a classic milestone in this great debt cycle and briefly review its operating logic.

My goal is to impart knowledge by sharing my thoughts on market mechanisms, revealing the essence of phenomena like teaching someone to fish—explaining the logical thinking and pointing out current dynamics, leaving the rest for the reader to explore. This approach is more valuable to you and avoids me becoming your investment advisor, which is more beneficial for both parties. Below is my interpretation of the operating mechanism:

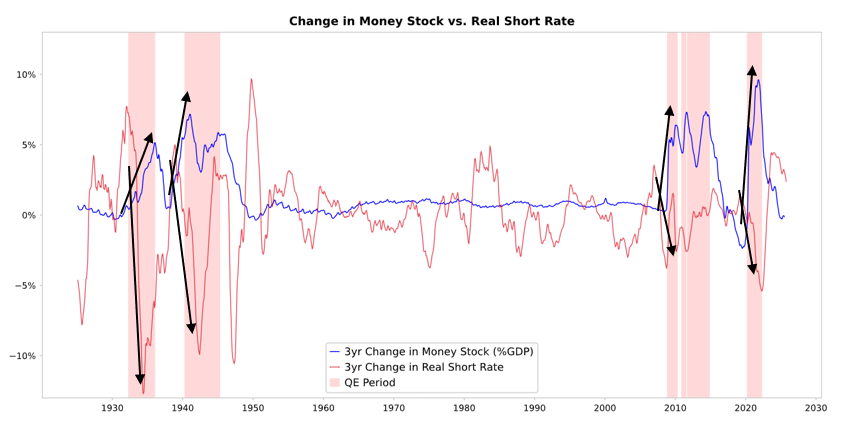

When the Federal Reserve and other central banks purchase bonds, they create liquidity and lower real interest rates (as shown in the diagram below). Subsequent developments depend on where this liquidity flows:

If assets remain tied up in financial assets, they will drive up asset prices and lower real yields, leading to an expansion of price-to-earnings ratios, a narrowing of risk premiums, and a rise in gold prices, resulting in "financial asset inflation." This benefits holders of financial assets relative to non-holders, thereby widening the wealth gap.

Typically, some liquidity is transmitted to the goods, services, and labor markets, pushing up inflation. However, with the current trend of automation replacing labor, this transmission effect may be weaker than usual. If the inflationary stimulus is strong enough, nominal interest rates could rise to a level sufficient to offset the decline in real interest rates, at which point bonds and stocks will face dual pressure on both nominal and real values.

Transmission mechanism: Quantitative easing is transmitted through relative prices.

As I explained in my book *Why Nations Go Bankrupt: The Great Cycle* (which I cannot elaborate on here), all capital flows and market fluctuations are driven by relative attractiveness, not absolute attractiveness. In short, everyone holds a certain amount of capital and credit (the size of which is influenced by central bank policy), and the flow of capital is determined by the relative attractiveness of various options. For example, borrowing or lending depends on the relative relationship between the cost of capital and expected returns; investment choices primarily depend on the relative level of expected total returns across different assets—expected total returns equal to the sum of asset yields and price changes.

For example, gold yields 0%, while the 10-year US Treasury yield is currently around 4%. If the expected annual price increase for gold is less than 4%, then holding Treasury bonds is the better choice; if the expected increase is more than 4%, then holding gold is the better choice. When assessing the relative performance of gold and bonds relative to the 4% threshold, inflation must be considered—these investments must provide sufficient returns to offset the erosion of purchasing power by inflation. All else being equal, the higher the inflation rate, the greater the increase in gold prices—because inflation primarily stems from the depreciation of other currencies due to increased supply, while the supply of gold remains relatively constant. For this reason, I pay close attention to the money and credit supply situation and the policy moves of central banks such as the Federal Reserve.

More specifically, in the long run, the value of gold always moves in tandem with inflation. The higher the inflation rate, the less attractive a 4% bond yield becomes (for example, a 5% inflation rate would increase the attractiveness of gold and support its price, while reducing the attractiveness of bonds as real yields fall to -1%). Therefore, the more money and credit central banks create, the higher I expect inflation to be, and the lower my preference for bonds will be compared to gold.

All else being equal, the Federal Reserve's expansion of quantitative easing is expected to lower real interest rates and increase liquidity by compressing risk premiums, thereby suppressing real yields and pushing up price-to-earnings ratios. This will particularly boost the valuations of long-term assets (such as technology, artificial intelligence, and growth companies) and inflation-hedging assets like gold and inflation-linked bonds. When inflation risks re-emerge, companies with tangible assets such as mining, infrastructure, and physical assets are likely to outperform pure long-term technology stocks.

Due to the lagged effect, inflation will be higher than originally expected. If quantitative easing leads to a decline in real yields while inflation expectations rise, nominal price-to-earnings ratios may still expand, but real returns will be eroded.

A reasonable expectation is that, similar to late 1999 or 2010-2011, a strong liquidity-driven rally will occur, eventually forcing tightening due to excessive risk. The liquidity frenzy before the bubble bursts—that is, just before the critical point when tightening policies are sufficient to curb inflation—is the classic ideal time to sell.

This time it's different because the Federal Reserve will create a bubble through loose monetary policy.

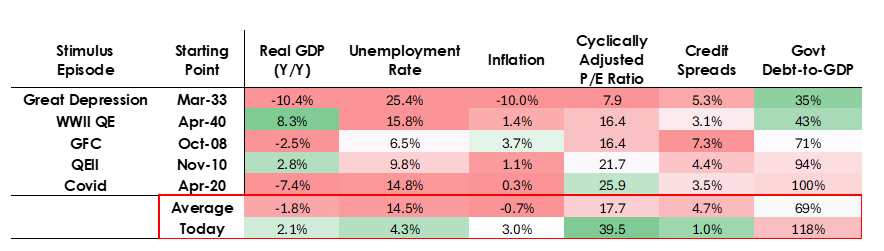

While I believe the operational mechanism will proceed as I described, the implementation environment for this round of quantitative easing is drastically different from the past—this easing policy is being implemented amidst a bubble, not a recession. Specifically, in the past, when quantitative easing was implemented:

- Asset valuations are declining, and prices are either low or not overvalued.

- The economy is in a state of contraction or extreme weakness.

- Inflation is at a low level or trending downward.

- The debt and liquidity problems are severe, and credit spreads are widening.

Therefore, quantitative easing is essentially "injecting stimulus into a recession".

The current situation is exactly the opposite:

Asset valuations are high and continue to rise. For example, the S&P 500 index has a return of 4.4%, while the nominal yield on 10-year Treasury bonds is only 4%, and the real yield is about 1.8%, so the equity risk premium is as low as 0.3%.

The economic fundamentals are relatively strong (the average real growth rate over the past year was 2%, and the unemployment rate was only 4.3%).

Inflation is slightly above the target (about 3%), but the rate of increase is relatively moderate, while inefficiencies caused by the reversal of globalization and tariff costs continue to push up prices.

Credit and liquidity are ample, and credit spreads are approaching historical lows.

Therefore, the current quantitative easing is actually "injecting stimulation into the bubble".

Therefore, this round of quantitative easing is not "injecting stimulus into recession," but rather "injecting stimulus into bubbles."

Let's look at how this mechanism typically affects stocks, bonds, and gold.

Because government fiscal policy is currently highly stimulative (as massive outstanding debt and huge deficits are being covered by massive issuance of government bonds, especially in the relatively short-term tranches), quantitative easing is effectively monetizing government debt rather than simply getting the private system flowing again. This makes the current situation different and also makes it look more dangerous and more likely to trigger inflation. It looks like a bold and dangerous gamble on economic growth, especially on artificial intelligence growth, funded by extremely loose fiscal, monetary, and regulatory policies, which we need to watch closely to handle properly.